One day in 1969, while walking along a corridor of the Paris metro, Breton artist Jacques Villeglé spotted an anonymous piece of graffiti on the wall bearing the name of then US President Nixon visiting de Gaulle in France. There were the three arrows of the former Socialist party for the N, the Cross of Lorraine for the I, a Nazi swastika for the X and a Celtic cross inside the circle of the Jeune Nation movement for the O. It was amidst the Vietnam War protests, and although the ideograms embodied violence, Villeglé’s intention wasn’t to elicit hatred any more than it was to trivialize it. At best, it was to shake up those who refused to face up to history, which was his central theme and his way of being of his time. Because the writing came from the wall and was anonymous, he concluded that it was well-suited to his artistic practice. He instantly and unhesitatingly appropriated it and continued to memorize different characters he stumbled upon to create his own graphic, universal socio-political alphabets, which have been constantly evolving to this day.

Jacques Villeglé installing his exhibition Alphabet(s) at the Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, 2021. Photo Tadzio / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Jacques Villeglé installing his exhibition Alphabet(s) at the Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, 2021. Photo Tadzio / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

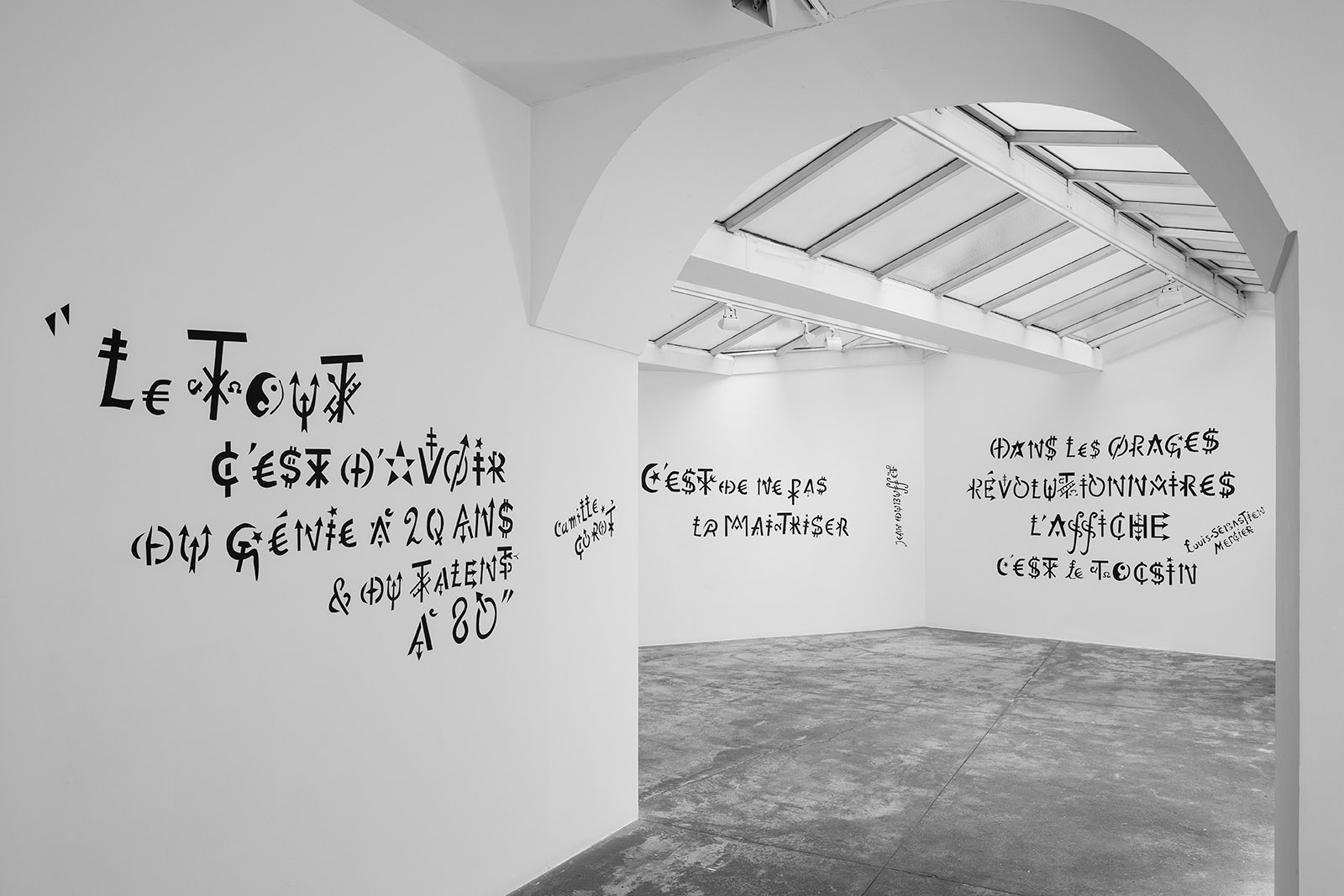

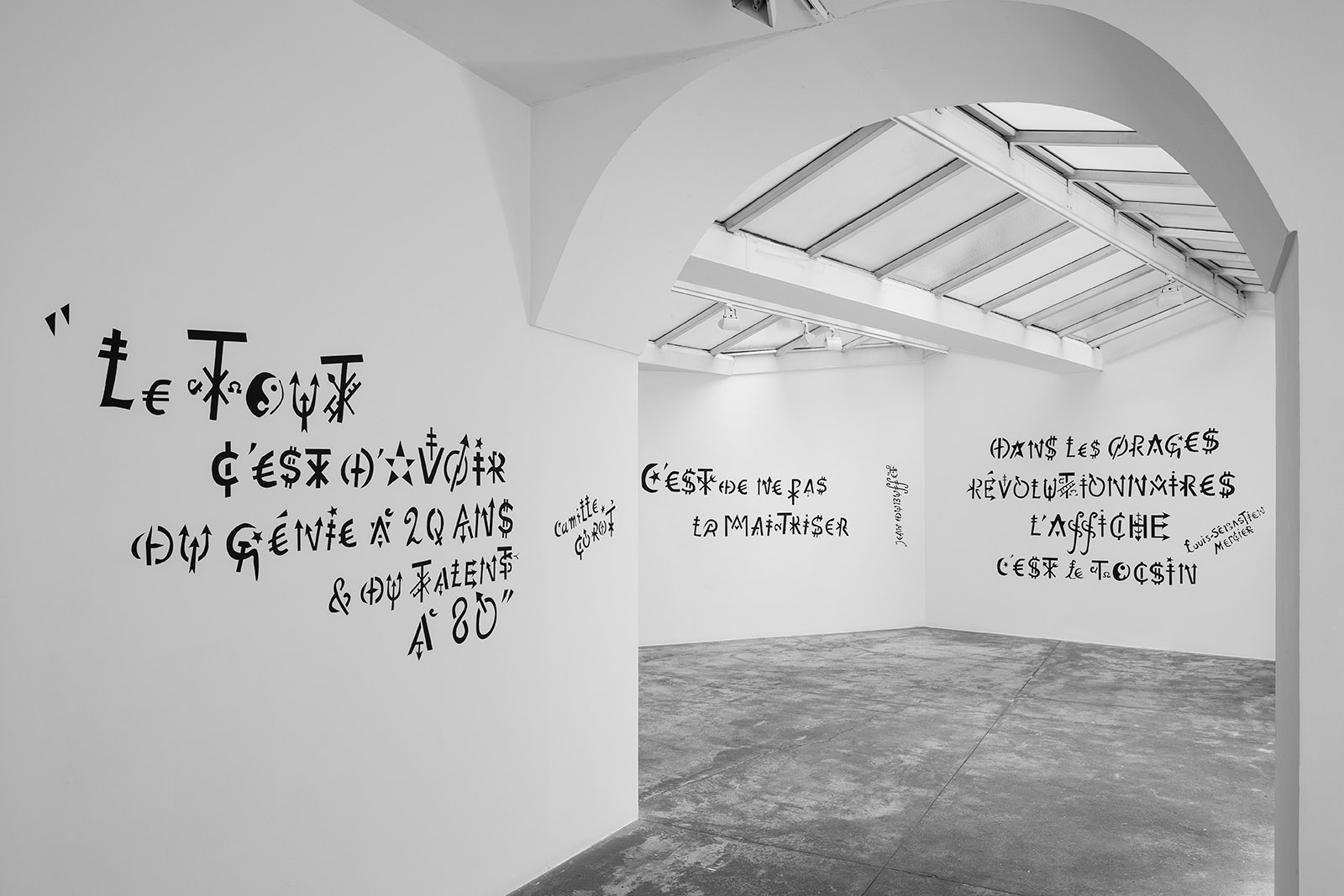

View of the exhibition Alphabet(s) at the Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, 2021. Photo Tadzio / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

View of the exhibition Alphabet(s) at the Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, 2021. Photo Tadzio / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Fascinated with complex languages since childhood, his alphabets have been his main focus since 2000, when he devoted himself to writing and drawing. He explains how he selects new letters: “I do not choose; I accept to integrate them into the alphabet.” He modified Roman letters, turning them into a mix of lines, circles, curves, and crosses, and gave symbols of political parties, religions, ideologies, movements, and currencies new meanings. He could combine the euro, British pound, yen, Star of David, and hammer and sickle.

Villeglé’s alphabets comprising heterogeneous signs and symbols became a painting. Borrowing sayings or phrases from others and transposing them onto paper, canvas, or wall, he invites the viewer to decipher his words and codes and therefore to become a cryptographer of the everyday traces of urban life. Today, the acuteness of his eye is just as extraordinary as when he first began.

At 95 years old, he’s still as contemporary and daring as ever. In Alphabet(s), his 11th and penultimate exhibition at the Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois Gallery in Paris held last in March – his first major gallery show based on this series – quotes by the likes of Marcel Duchamp, Jack Kerouac, and Camille Corot were painted on the walls. We found “Let’s be realistic, demand the impossible” by Che Guevara; “What matters in a technique is not to master it” by Jean Dubuffet; “Do not be afraid of the past. If people tell you that it is irrevocable, do not believe them” by Oscar Wilde; “It is not enough to have beautiful letters to write a real alphabet” by Jacques Prévert; and “Eternity is a long time, especially towards the end” by Woody Allen.

Villeglé is best known for making art from scraps of layered, torn posters retrieved from urban landscapes. For a half-century, he roamed the city in search of anonymous, deteriorated posters with a strong visual impact to turn into paintings. Rather than traditional practices of painting or sculpting, he wished to create something new, so he cut out ripped posters from public billboards and hoardings, brought them back to his studio, reconstituted them and glued them onto canvases. “I did not try to criticize society, but to illustrate it in an original way,” he says. “While I was interested in abstract painting, I regretted that nothing in everyday life could interest artists. I knew the history of the evolution of posters and had noticed that designers-creators took pleasure in working on their compositions, drawing inspiration from those of Cubist painters, among other things. This parallel didn’t displease me.”

Over time, he waited for these advertising and concert posters to evolve, and his work along with it. Villeglé was one of the founders of New Realism, an art movement established in 1960 based on a term coined by French art critic Pierre Restany, and whose members included Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle. Although they worked in varied visual art disciplines – compressions (César), accumulations (Arman), assemblages (Martial Raysse) and packaging (Christo) – they perceived a common basis for their work: A method of direct appropriation of reality. They recovered discarded items, using trash, cars, concrete and sheet metal as new mediums, thereby transforming everyday objects into symbols of the revival of post-war consumption, and deliberately excluded “noble” materials such as bronze or stone. Restany called Villeglé a recycler of others’ work and of the urban, industrial, and advertising reality. Also a recycler of himself, his creations constantly need to be moulded and reformulated.

Jacques Villeglé, Oui – Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, 22 October 1958, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 68 x 100 cm, private collection. Photo François Poivret / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Jacques Villeglé, Oui – Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, 22 October 1958, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 68 x 100 cm, private collection. Photo François Poivret / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

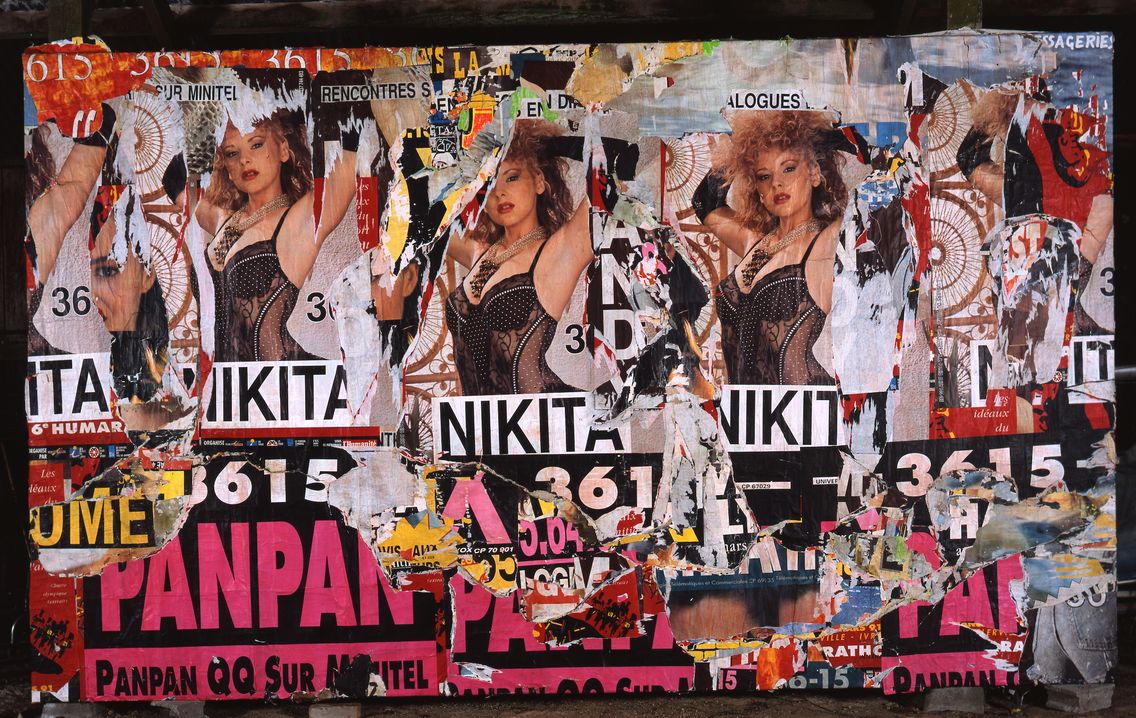

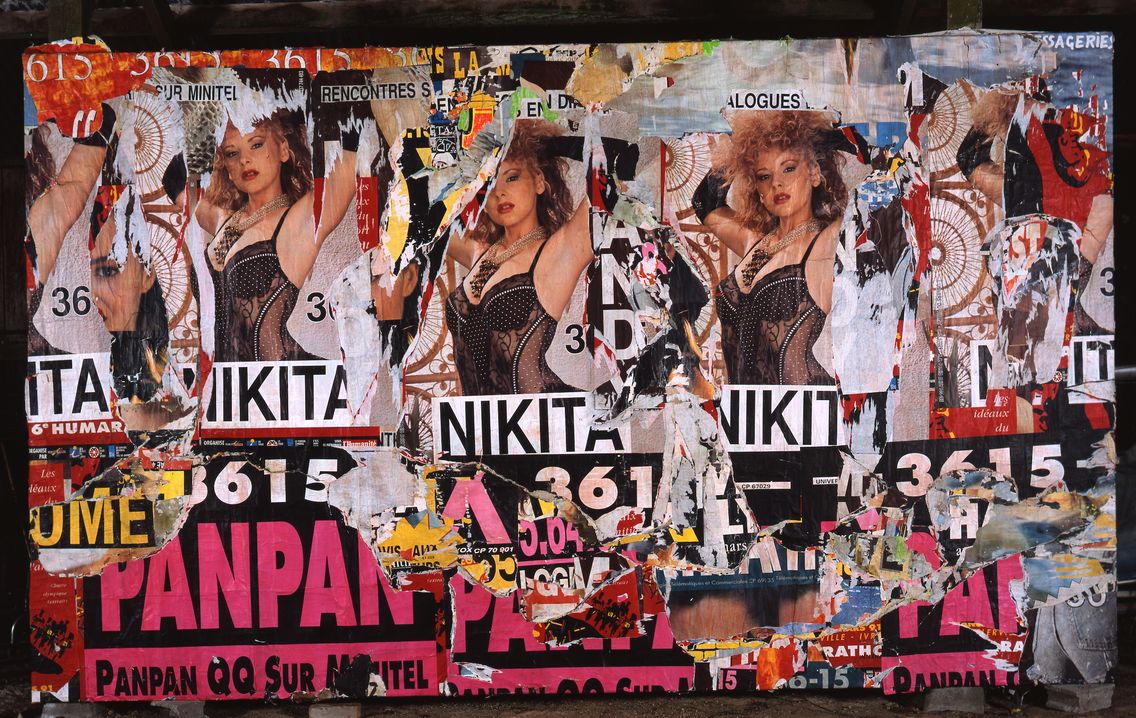

Jacques Villeglé, Rue Réaumur – Rue des Vertus, 4 June 1984, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 159 x 228 cm. Photo Serge Veignant / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Jacques Villeglé, Rue Réaumur – Rue des Vertus, 4 June 1984, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 159 x 228 cm. Photo Serge Veignant / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Since 1949 when Villeglé invented the process of lacerated posters, with the black-and-red Ach Alma Manetro artwork gleaned from a giant 6 x 25 meter palisade between Le Dôme and La Coupole restaurants in Paris’ Montparnasse, accompanied by fellow French artist Raymond Hains, whom he had met at university, he has been creating artworks that document the era in which he lives and tell the story of his generation like a world newspaper of the streets. Titling his works the addresses of where he had hijacked the posters from, he knew they would constitute a memory of the city, like an archaeologist bringing back his excavations. Instead of an idea, it was about a gesture because he had read a philosopher’s reflection saying that there is evolution in art when there is economy of labour. Everything had already been done for him by poster designers, anonymous passers-by who ripped or traced graffiti onto the posters and the rain and sun; he would just conceive the composition. A collector and historian of sorts, he extracts barely-legible fragments from the life of the streets, which he saves from oblivion.

His wide-ranging works have chronicled the Algerian War of Independence or the erotic messaging service of the Minitel Rose in France. “I transformed lacerated posters into works of art; that was my goal,” he insists. “I christened them ‘the anonymous tear’ because, according to a certain dialectic, a lacerator is a lacerated being. I chose the posters for the interest of their composition, then for the interest of a word, a fragment of a sentence and, in the 1960s, for their colors.” For him, laceration wasn’t a destructive act; it was to build a new type of beauty.

Profoundly connected with the urban landscape and an admirer of graffiti, Villeglé has always enjoyed the ambiguous nature of the language of the street. “What I have in common with street artists is an interest in the culture of a city,” he discloses. “I’ve spent time with them because of our mutual interest in current life. Additionally, they are much younger than me, so it’s flattering and I take great pleasure in meeting them. I like artistic society and I feel an interest in my work among street artists. It is more a mentorship than a collaboration. I get along well with them; they save me from loneliness.”

Jacques Villeglé, Bas-Meudon, 28 January 1991, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 280 x 475 cm. Photo François Poivret / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Jacques Villeglé, Bas-Meudon, 28 January 1991, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 280 x 475 cm. Photo François Poivret / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Although considered the father of street art, Villeglé almost always drew inspiration from the streets rather than adding his touch to them. However, his alphabets occasionally find their way back to the walls and asphalt from which they originated in artistic installations, revealing this lone figure who borrows from, but also gives back to the city.

Take for example when he inscribed the words “To be astonished is a pleasure” by Edgar Allan Poe as a large graphic stencil installation on a wall in Paris’ Tuileries Garden in 2009, or the phrase “Art is what helps draw us out of inertia” by Belgian writer Henri Michaux on the street in front of the Grand Palais in 2016 during the FIAC international art fair in the French capital. “Artistic works will be a testimony of a bygone era,” he concludes. “Artists work to create these testimonies. The spirit of New Realism was partly only a conversation with society. It is a group of friends of the same generation, each having a different and perhaps even contradictory viewpoint. The artist hopes that his work will give his successors the desire for dialogue.”

Jacques Villeglé installing his exhibition Alphabet(s) at the Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, 2021. Photo Tadzio / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Jacques Villeglé installing his exhibition Alphabet(s) at the Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, 2021. Photo Tadzio / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

View of the exhibition Alphabet(s) at the Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, 2021. Photo Tadzio / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

View of the exhibition Alphabet(s) at the Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, 2021. Photo Tadzio / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Jacques Villeglé, Oui – Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, 22 October 1958, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 68 x 100 cm, private collection. Photo François Poivret / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Jacques Villeglé, Oui – Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, 22 October 1958, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 68 x 100 cm, private collection. Photo François Poivret / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Jacques Villeglé, Rue Réaumur – Rue des Vertus, 4 June 1984, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 159 x 228 cm. Photo Serge Veignant / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Jacques Villeglé, Rue Réaumur – Rue des Vertus, 4 June 1984, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 159 x 228 cm. Photo Serge Veignant / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Jacques Villeglé, Bas-Meudon, 28 January 1991, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 280 x 475 cm. Photo François Poivret / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Jacques Villeglé, Bas-Meudon, 28 January 1991, lacerated posters mounted on canvas, 280 x 475 cm. Photo François Poivret / Courtesy of Galerie GP & N Vallois, Paris

Back

Back