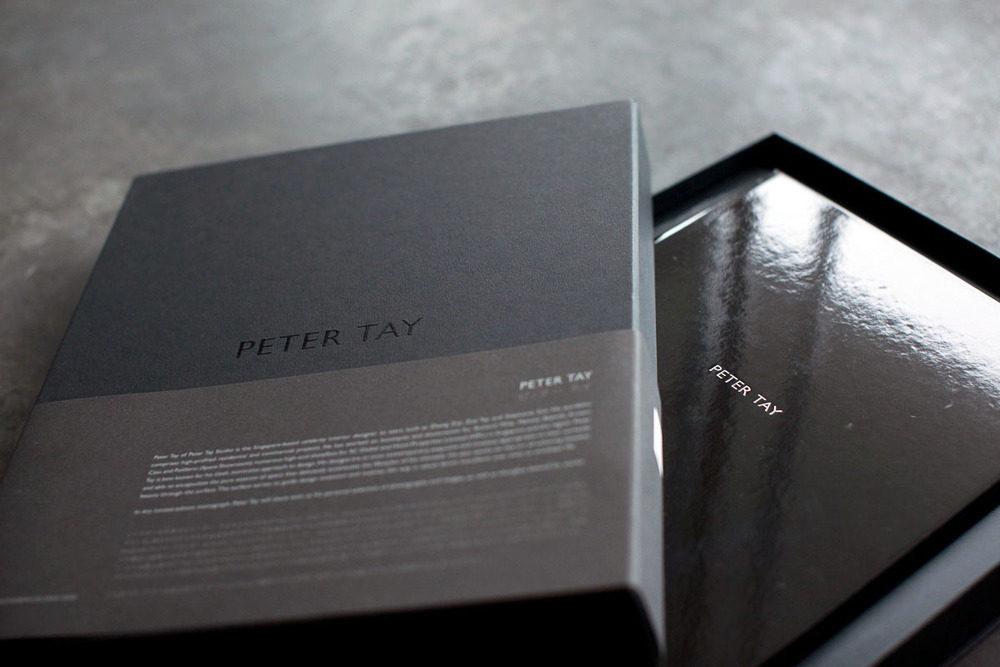

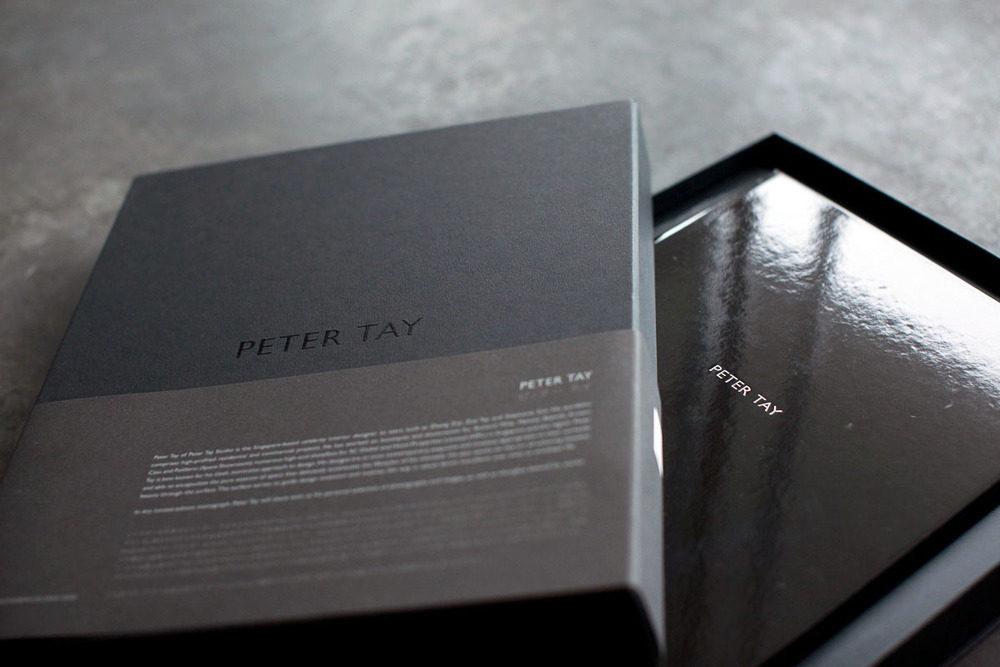

The first monograph on Peter Tay’s works came out in 2013. Published by Sanctuary Niseko in Japan, it was a hefty volume that came in a thick cardboard box, its cover a gleaming black field with just the title, Peter Tay, stamped in silver foil in sans serif font.

The sides of the book were hand-painted with black ink, and when you opened each page for the first time you'd hear a distinct crackling sound. You consider the size of the book that is large enough for a tea service and you decide that it was all deliberate – the hard case, the glossy cover, the crackling sound.

(Image from Peter Tay Studio)

(Image from Peter Tay Studio)

Designed by Ms. Jacinta Sonja Neoh, the book didn’t have much text; it’s clear from the get-go that it was going to be a visual trip. Peter told his story in the first few pages before the parade of twenty selected projects, each one with a brief introduction preceding a series of photographs, commenced.

Prof. Erwin Viray, who was both editorial adviser and editor, wrote a page’s worth of text which ran near the end of the book like an epilogue. The rest of the volume was filled with photographs by Mr. John Heng.

Most of them were representational, capturing moods and evoking moments rather than showing off interior design that many people doubtless expected.

And who could blame them? If one of Singapore’s most talked-about interior designers put together a book, a shiny catalog with clear photographs and comprehensive captions wouldn’t be amiss.

But obviously, the team behind the project had something else in mind: A distillation, not so much an analysis, of Peter’s works.

And so, there were images of a wall reflected on a pool of water, a living room mirrored on a shiny ceiling, a fine antique boiserie that Peter had bought in France and reassembled in a fashion boutique in Shanghai, a pretty young woman partly hidden from view by a rack of jackets. There was also a portrait of Peter, a candid shot as one would call it, smiling at something that we couldn’t see.

Even the straightforward photographs of hallways and corridors and living rooms were bathed in emotion. The pillow on a leather daybed had the indentation of a head, a set of outdoor furniture was strewn with fallen leaves.

Lives were surely being lived in those rooms with glossy surfaces and endless views. If anyone who was sitting in one of those super-penthouses, perhaps on a B&B Italia leather couch, framed by a Boca do Lobo bar cabinet on one side and a Zheng Xiaogang painting on the other, happened to gaze on a lacquered wall across the room, he would see the reflection of a random moment that would likely make it in the book.

It was an exquisite volume, an exhaustive work, and definitely a tough one to follow.

So, when I bumped into Peter at a party, and he told me about his plans for a second monograph, I became curious. Has it been that long since the first volume came out? And does he really have new stories to tell?

- A STORY OF THREE THEMES

- AT EASE WITH LUXURY

- UP FOR A SECOND

A Story of Three Themes

In all his years as an interior designer, Peter Tay’s story lines have somehow been reduced to just two: that he has a roster of very wealthy and celebrity clients, and that he survived a near-fatal accident.

Fairly or not, those two have been milked for whatever they were worth; you could hardly find a longform article about Peter that does not attempt to regale you with what Wang Lee Hom’s studio looks like or what really happened on that fateful October morning twelve years ago.

His "signature style" of using reflective surfaces in his design has also surfaced as a third narrative strand, one that is often lavishly illustrated with photographs.

But the fact that Peter has crafted some of the most exciting interiors, not just for the Nth home of a tycoon or an intimidatingly chic boutique, is sadly often buried in the intervening paragraphs.

People often forget that in Cambodia, Peter has designed a church, and gave it as much of himself as his other high-profile projects, although the work – and this Peter adds sotto voce – was pro bono.

“I wanted to give the churchgoers a sanctuary, a place where they can come and feel safe and peaceful. I wanted those feelings to stay with them whenever they thought of their church, not just during the hour-long service.”

If you ask him about the latest penthouse or show unit he has completed, he would recite the same lines: “I want my clients to feel safe and secure and comfortable;” the bespoke furniture, the book-matched marble top, the artwork handpicked in a gallery abroad on his advice matter little.

Peter himself has confessed to a disinterest in the one-to-one correspondence of architectural renderings. As a young architecture student at the University of Western Australia, he drew stories and ideas about spaces while his classmates produced on-scale architectural plans.

And during his entrance interview at the Architectural Association of London, he talked about the ideas behind his drawings, how he imagined people using and living in them. Clearly, the creation of a sanctuary, where people thrive and flourish, has been and remains his true objective.

A Peter Tay Studio project at Jiak Kim Street

A Peter Tay Studio project at Jiak Kim Street

- A STORY OF THREE THEMES

- AT EASE WITH LUXURY

- UP FOR A SECOND

At Ease with Luxury

“Every day that I came out of AA, I would go to Chinatown through Shaftesbury to hunt for a Chinese restaurant,” Peter once told me. “You can’t imagine how much I missed Chinese food; I could only afford the cheapest places and their cheapest dishes but that was good enough.”

He was then living in a council flat in London’s Zone 3, a rough neighbourhood far away from the city center where violent crimes were not unusual.

Those ten-minute walks from school to Chinatown would become an important ritual of his student life in London.

“I always felt that I needed to do it. I would pass by Covent Garden and make my way to St. Martin’s. I might stop at Joseph’s store to see what they had in the windows, but I never bought anything.”

He came expressly to see things: The bookstore displays that changed every week, the photographic exhibition in a shop next door, the montage of model cars in another. None of them were done by a designer, Peter remembers, but they were very meaningful and beautiful, at least to him.

Walking on those streets, he saw art, fashion, design in plain light – things coming together within their own context, their own milieu. “And then I would linger outside the St. Martins Lane Hotel, which was then newly designed by Philippe Starck.”

Whatever money he had saved up went to vintage designer furniture that he started collecting: mid-century modern masterpieces by the likes of Prouvé, Perriand, Le Corbusier, and Mouille that he hunted down in second-hand shops and auction houses across Europe.

Otherwise, he absorbed as much as he could of his foreign surroundings, and promised himself to be as good as he could be or at least to work as hard as he can.

People who meet Peter today for the first time are affected by his ways with the idioms of luxury. He seems to have been conversant with it all along, perhaps having been born into money. Although he was never poor, he knew innately where to train his eyes and which sacrifices to make.

A Peter Tay Studio project at Goodman Road

A Peter Tay Studio project at Goodman Road

- A STORY OF THREE THEMES

- AT EASE WITH LUXURY

- UP FOR A SECOND

Up for a Second

“The new monograph will be in a metal case; I will put dents on each one by hand, maybe with a hammer,” Peter tells me. He sounds excited.

“When they pull the book out of the case, it will be… pristine, luxurious, a work of art….” I think it is somewhat distasteful to allude to the accident in this way, if that is indeed the intention, but I’ve heard stories from Peter that initially didn’t make sense until I saw the final result and was blown away just the same.

I look at Peter and imagine how the titanium structure that holds up and gives his face its shape, the scar that runs across the top of his head, his eyes that were crossed when he first opened them as he emerged from coma, and how he still can’t smell anything to this day. It’s hard to imagine what he has been through, yet here he is across my desk talking about the accident and how it could possibly be worked into his planned second monograph.

This time he has convened heavyweights to collaborate on the project – Mr. Theseus Chan is said to have cleared a portion of his calendar to design it, and Prof. Viray and Mr. Heng are expected to reprise their roles as writer-editor and photographer, respectively.

Other names have been mentioned previously in connection with the project, but the final team seems set for now. The plan is to have limited-edition boxed prints and controlled-edition print runs.

It will be printed in Japan and launched in Singapore in May, Peter’s birthday month, at a venue that is being decided at the moment.

As I listen to Peter almost gushing about his second monograph, I gain a new insight into why the accident recurs in his story. Firstly, the tabloid-worthy details are hard to ignore: An architect on the rise crashing his black Toyota Supra into a tree somewhere in the east while on his way to a mid-morning meeting; motorists passing by certain that no one could have survived the wreckage; a client, a well-placed person in the medical industry, personally assembling ten specialists to perform a gruelling 24-hour surgery; a stream of celebrities and prominent people taking turns to visit Peter at Singapore General Hospital finally revealing to the staff who he really was.

It was not simply a matter of survival; it was a conviction to live. He had the support of his family and friends, but he also had the will to open his eyes after three weeks of being comatose and face the aftermath in the hospital tethered to machines and feeding tubes for an entire month.

When I press Peter for details of the accident, he sounds joyful rather than stoic. “It gave me a new way of seeing things,” he says.

“I have come to look at life and how we can spend it very differently. We may not have time – everything comes to an end – but while we’re here, we have the opportunity to look into things, and be deliberate with what we do with our time.”

A Peter Tay Studio project at South Beach Residences

A Peter Tay Studio project at South Beach Residences

A Peter Tay Studio project at Jiak Kim Street

A Peter Tay Studio project at Jiak Kim Street

A Peter Tay Studio project at Goodman Road

A Peter Tay Studio project at Goodman Road

A Peter Tay Studio project at South Beach Residences

A Peter Tay Studio project at South Beach Residences

Back

Back