Cartier recently unveiled new creations within its Panthère de Cartier collection earlier this year, which includes a La Panthère bracelet in yellow gold, onyx, emeralds and brilliant-cut diamonds, in a continuation of the style signature that has been associated with the maison since 1914.

Comprising 11 rings, six bracelets and one brooch, the new pieces feature a refreshed interpretation of the iconic feline, a new design that is a thinner version of the current Panthère de Cartier designs but sports the same “fur” setting on the diamond pieces.

The incoming pieces mark an inflection point from those that have come before, leading them to be described as “the contemporary feline expression of a free, elegant and sensual femininity.” This brings the collection to 59 items, made up of jewelry, watches, accessories and perfumes.

The collection’s sleek, modern interpretation of the panther may belie the fact that it has been more than a century since the feline entered the lexicon of Cartier, at a time when large cats were a popular motif among artists, from François Pompon to Rembrandt Bugatti to Paul Jouve.

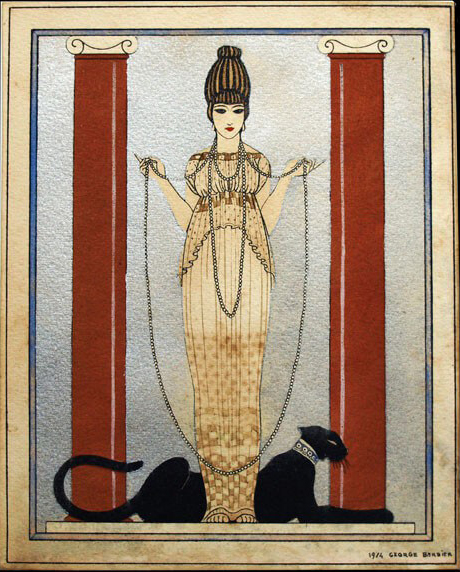

The panther made its debut in the Cartier universe in 1914 via a jewelry exhibition invitation card “Dame à la panthère,” commissioned from artist George Barbier; that same year, Cartier Paris created a ladies’ wristwatch in platinum and pink gold, decorated with a spotted pattern of diamonds and irregularly shaped onyx pieces.

Cartier designer Charles Jacqeau was one of the first in the maison to work with the panther coat motif. Then, the feline was recreated in two-dimensional profile to adorn the cover of vanity cases that Cartier crafted between 1925 and 1930.

Other contemporaneous objects of note include a 1915 watch-brooch in platinum set with onyx and diamonds, subsequently sold to Pierre Cartier, and a 1930 bracelet in platinum and gold, with black enamel and strands of fluted coral beads, and onyx spots interspersed among round old- and single-cut diamonds on the clasp.

Since then, highlights from Cartier bearing the panther emblem have displayed its sleek, majestic form perched insouciantly in brooches; its spotted fur recreated with pavé diamonds, onyx, sapphire and lacquer on necklaces and bracelets; and its gleaming eyes and imposing mien peering intently from watches and rings.

One person who could be credited with single-handedly cementing the panther’s position in the iconography of Cartier is Jeanne Toussaint, who joined the maison in the late 1910s and served as creative director of Cartier’s jewelry department from 1933 to 1970. Fond of bold prints and exotic inspirations — red Tatar boots and Chinese silk pajamas were part of her wardrobe — Toussaint had style in spades and possessed a taste for the unconventional, such as pairing yellow gold with vibrantly colored gemstones.

After they went on a safari tour in Kenya, she and Louis Cartier introduced panther-inspired jewelry. Toussaint’s own nickname, “La Panthère,” was earned through having to assert herself as an authority at Cartier (a challenge considering women in France could not vote until 1945) and her personal fondness for the feline, whose form embellished some of the jewelry, vanity cases and boxes she owned.

But her appreciation for the large cat went beyond the beauty of its coat; she admired it as a symbol of power and fearless independence, which was particularly pertinent at a time when she likely sensed that society was on the cusp of a new era of modernity, femininity and freedom of expression.

In 1948, as part of a gold and black enamel brooch fashioned with a 116-ct emerald cabochon intended for the Duchess of Windsor Wallis Simpson, Toussaint rendered the three-dimensional panther in its entirety, a first for Cartier. The following year, the duchess acquired another Cartier brooch featuring a three-dimensional panther, this time made of platinum, white gold, diamonds, sapphire cabochons spots, and one 152.35-ct Kashmir sapphire cabochon.

The panther motif was soon embraced by contemporary style icons, such as Mexican actress María Félix, French socialite Daisy Fellowes, and Princess Nina Aga Khan.

In the 2013 tome “Cartier Style and History,” Hubert de Givenchy called Toussaint’s style “very personal, very particular, very Cartier” and her creations “universally admired because they are lively, avant-garde and extremely elegant.” “She revolutionized luxury jewelry by rejuvenating and modernizing it, much in the manner of a great painter, not only playing with very beautiful precious stones but also displaying great innovation in her creations,” he added.

One key feature integral to Cartier’s lifelike panther emblem is the maison’s own “fur” setting technique, which recreates the appearance of the panther’s fur through gemstones, such as onyx and sapphire for the spots: Each stone is cut to measure, then sorted and set into a lattice, with fine metal threads folded toward each stone to hold it in place.

Bringing the panther to life also means paying intense attention to detail, to achieve a faithful representation of every one of its features and evoke its majesty and poise. In 1927, Cartier designer Peter Lemarchand spent lengthy periods observing the panthers at the Vincennes Zoo as research for fashioning realistic versions out of precious materials, and the well-worn copy of Mathurin Méheut’s “Études d’animaux” in the Cartier library for designers showed that the figures of panthers were frequently referenced and intently studied by the maison’s creative masters.

Though its personality and expression have evolved over the decades — from fearsome in the 1950s to playful in the 1960s to faceted and futuristic in the 21st century — the panther motif remains a vital signature of the maison.

“For over 100 years, no other creature has achieved such iconic status, whether at Cartier or in 20th-century jewelry as a whole,” says Cartier Heritage Director Mr. Pierre Rainero. “No other creature or jewel is so indissolubly and emotionally linked to the stylish women of the 20th century, the 20th-century female ideal, or the Cartier legend.”

"The Woman with the Panther", stencil by George Barbier for the invitation card to Cartier's "exhibition of a unique collection of pearls and jewelry of ancient decadence", 1914 (print copy). Source: diktats.com

"The Woman with the Panther", stencil by George Barbier for the invitation card to Cartier's "exhibition of a unique collection of pearls and jewelry of ancient decadence", 1914 (print copy). Source: diktats.com

Cartier wristwatch with panther spot motifs from 1914

Cartier wristwatch with panther spot motifs from 1914

María Felíx in Cartier Panthère jewelry, 1917. Source: Anothermag.com

María Felíx in Cartier Panthère jewelry, 1917. Source: Anothermag.com

La Panthère bracelet in 18k white gold, set with 923 brilliant-cut diamonds totalling 10.3ct, emerald eyes and onyx, reminiscent of the double-headed panther bangle that belonged to Princess Nina Aga Khan

La Panthère bracelet in 18k white gold, set with 923 brilliant-cut diamonds totalling 10.3ct, emerald eyes and onyx, reminiscent of the double-headed panther bangle that belonged to Princess Nina Aga Khan

Back

Back