The result is ‘Into Air’ – a beguiling body of work with three chapters. ‘Clocks’ features photographed colored ice blocks; ‘Time Lost Falling in Love’ is a set of time-lapse films of the blocks melting; and ‘Ash resurrects the melted ice from their watery graves into parallel paintings of static tributaries. That three diverse mediums are employed is intriguing. These works debuted in January during a solo exhibition ‘Into Air’ in an old ship-repairs workshop in Jalan Besar, whose timeworn setting suits the theme.

For the past three years, Dawn Ng has been studying the various states of water. The artist hauled ice chunks from industrial freezers installed in her studio, stacked and tilted them like a child play-testing blocks, tinged them with assorted hues, analyzed and recorded reactions borne from temperature, time and elemental differentiation in detailed spread sheets, and participated in acts of chemical destruction to paper.

.jpg) Photo by Caline Ng,

Dawn Ng at 2 Cavan Road, where she held her exhibitions Merry Go Round (2020) and Into Air (2021)

Photo by Caline Ng,

Dawn Ng at 2 Cavan Road, where she held her exhibitions Merry Go Round (2020) and Into Air (2021)

Photo courtesy of Dawn Ng studio,

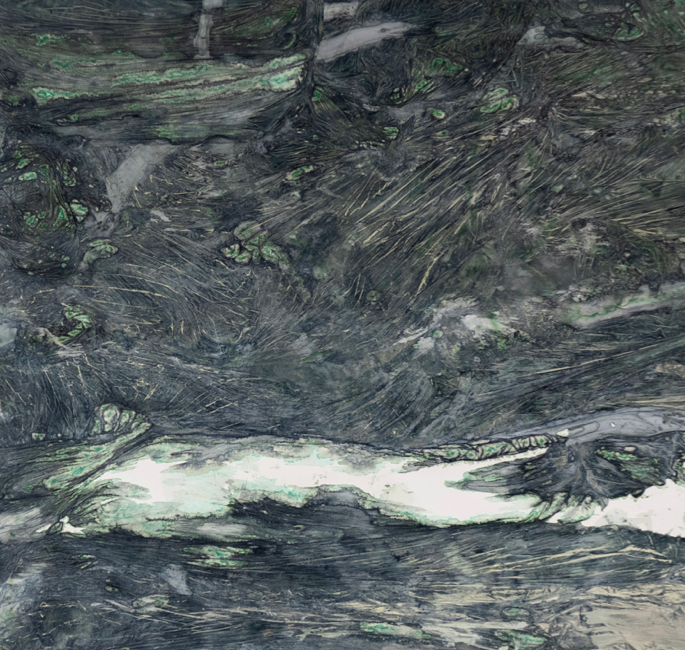

Into Air is a three-part art journey on the theme of time, with Ash as the final part that immortalises the residues of melted ice onto canvases. One of the pieces exhibited in her January solo exhibition was Odessa (2021)

Photo courtesy of Dawn Ng studio,

Into Air is a three-part art journey on the theme of time, with Ash as the final part that immortalises the residues of melted ice onto canvases. One of the pieces exhibited in her January solo exhibition was Odessa (2021)

Photo courtesy of Dawn Ng studio,

Where have all the flowers gone (2021) from Ng's 'Clocks' series from Into Air that was exhibited at the January 2021 solo exhibition organised by Sullivan+Strumpf, the gallery that represents Ng

Photo courtesy of Dawn Ng studio,

Where have all the flowers gone (2021) from Ng's 'Clocks' series from Into Air that was exhibited at the January 2021 solo exhibition organised by Sullivan+Strumpf, the gallery that represents Ng

I visit Ng in her sun-washed studio one morning. Her many chromatic examinations past and present enliven the ivory walls. Color is important in her work, the artist affirms. “My use of them is intuitive, and I am often trying to unfurl a feeling with a gradient. I am obsessed with them – all the ones we have names for, and even more so the ones we don’t,” gushes the artist who veers toward white in her dressing “for mental clarity; I think so much about colors in my work that I can’t quite stand it on myself.”

During my visit, Ng, who is represented by Sullivan+Strumpf Fine Arts was assembling pieces for the January exhibition. Large prints drape nonchalantly over pastel-and-mirror structures from her 2016 installation ‘How to Disappear into a Rainbow’ for Hermès’ art space Aloft. On the floor, a photographed ice block and its less saturated residue painting rest in wooden vats. The series came about by dint of Ng’s restless meditations on time. It accompanies recurring themes of space, collective memory and identity rooted in a displaced homecoming from art school studies (Slade School of Fine Arts, University College, London, and Georgetown University in Washington DC) and overseas stints in branding and advertising.

Photo by Dawn Ng,

Walter (2009) was one of Ng's early pivotal works that aimed to bring a refreshing perspective to Singapore's ubiquitous urban settings with an inflated rabbit

Photo by Dawn Ng,

Walter (2009) was one of Ng's early pivotal works that aimed to bring a refreshing perspective to Singapore's ubiquitous urban settings with an inflated rabbit

The sightings of ‘Walter’ (2010) – a giant, inflatable bunny – in mundane spaces celebrated Singapore’s ubiquitous fabric; ‘Perfect Stranger’ (2018) was a highly personal spatial and narrative work immortalizing correspondence with a child psychologist the year she was pregnant, to be bequeathed to her daughter in the future; and ‘11’ (2020) at Telok Ayer Arts Club employed role-play to seed affinity between strangers. By comparison, the medium of ice is innocuous.

“We’re all ephemeral objects – you and I – and I guess aging is how we disintegrate. I thought of ice as the perfect material because living in the equator, the second you take an ice cube out of a cold environment, you start losing it, and part of that process of time passing through space is compacted into a moment,” she says. Ice’s transient nature rebels against our archetypal modes of reading time. “The ways we understand time is mathematical, chronological, linear, numerical – quite sterile really. The day we’re born, we’re time stamped, even down to how we live our lives, scheduling [programs] into our lives. But when you think about it, time is entirely emotional and elastic; time speeds up when you’re having fun, slows down when you wait, and stands still when you fall in love with, say, a person, place, or song,” Ng ruminates.

For months, she conducted laboratory style trials on ice blocks – some over 60kg – in her bid to physicalize time. “What does 3pm look like in a color, shape, or form? What is the residual carcass that 15 hours leaves behind?” she pondered. After shaping her glassy, colored creations, she left them to melt and photographed each three times over their metamorphosis from solid to liquid. Viewed in sequence, their shape shifting evokes fantastical lunar eclipses.

The first 30 out of more than a hundred attempts were vital precedents. “They taught me about how different [agents] behave in such extreme conditions. Acrylic tends to get a bit chalky and coagulate, whereas frozen dyes and inks have a glacial translucency, which I fell in love with,” she shares. These and other lessons birthed the vocabulary for more designed iterations. For instance, she avoided using acrylic in a part of a block she wanted to be clear. “It’s like forming my own element table,” Ng quips.

Composing with ice was a new experience for Ng that entailed a degree of relinquishing control so foreign in her exacting work. “Sculpting stone is a process of reduction, but this was actually a process of addition, with time doing the reducing,” Ng explains, pointing out an unpremeditated wedge shape in a block formed by tilting the block’s Styrofoam casing.

This was also the first time Ng made time-lapse films as art. The smooth-flowing waterfalls belie tedious filming of up to 18 hours for each block’s full liquefaction. Editing was equally tricky. “A big block melts faster than when it is small, so time actually stretches longer toward the end. The time it took to melt also depends on conditions like the daily studio temperature and pigments used,” says Ng. She switches on a television screen propped portrait-up to show me one. It is hypnotic to watch the block thawing in fast forward, glistening like an astral object. While unintended, the films became a sort of hourglass. Muses Ng, “These films range from 20 to 30 minutes each, so I know how long people stay in the studio based on how long the film runs.”

The paintings created with the melted ice was her quest to close the loop from solid to air “like how we go back to nothingness” upon death. “If ‘Clocks’ was a process of trying to stop time, and the films of bending time, this last step was about sieving time,” she expounds. In wooden vats, she laid thick watercolor paper to soak up the residue until they fully evaporated. At times she added or subtracted residues, and layered cling wrap to shape patterns. Says Ng satisfyingly, “the paper took on a different texture because the fibers were so broken down; there was that true feeling of decay.”

The long-drawn sojourn led to acceptance that some things like time cannot be caught. “You just have imprints and memories,” she contemplates. If anything, having chance play a part in the outcomes was “fun and cathartic.” This ‘letting go’ is strangely prescient with the sense of helplessness brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. But instead of ennui, Ng ravelled in the back-to-basics shift.

Photo by Jovian Lim,

Merry Go Round (2020) was an installation held as part of last year's TWENTY TWENTY art exhibition that invited visitors to experience the confounding phenomenon of collapsing dimensions and the unravelling of time with splintered images of oneself

Photo by Jovian Lim,

Merry Go Round (2020) was an installation held as part of last year's TWENTY TWENTY art exhibition that invited visitors to experience the confounding phenomenon of collapsing dimensions and the unravelling of time with splintered images of oneself

Everyday during the circuit breaker, Ng rose at dawn to mix paper, tissue, glue, and gypsum in her makeshift home studio, and constructed vessel after vessel with paper mâché. Sixteen were listed on art web shop The Artling this year and were snapped up quickly. “Compared to the last few projects that I was working on, with a scale such as ‘Merry Go Round’ (2020) or technicality like ‘Into Air’ that I could not do alone, this series brought me back to the process of using just my two hands. The vessels are petite objects that you can cradle [but almost crush],” says Ng of their paradoxical structuredness and fragility.

“Growing up, my mother would nag at me, saying ‘if you can’t do small things well, how can you go on to do big things?’ We couldn’t do big things during the circuit breaker, so instead of doing nothing, we can do small things,” says Ng, who named the collection ‘Small Things’. This tender chiding has grounded the artist’s modus operandi, enabling her to wizard up meticulous works that bestow life and emotion upon the prosaic and forgotten.

Back

Back