In celebrated designer Bruno Munari’s tome “Design as Art,” he talks about the designer’s responsibility to make even the most utilitarian encounters inspiring. “There should be no such thing as art divorced from life, with beautiful things to look at and hideous things to use.

“If what we use everyday is made with art, and not thrown together by chance or caprice, then we shall have nothing to hide … anyone who uses a properly designed object feels the presence of an artist who has worked for him, bettering his living conditions and encouraging him to develop his taste and sense of beauty,” he writes.

This apartment renovation by Singapore-based interior design studio UPSTAIRS_ reminds me of these words. The sense of care given to every space and element is keenly felt.

The result is an effortlessly elegant home for a couple, their teenager, and a live-in helper. Entering Ryokan Modern, one immediately rises to a state of heightened attention typically evoked by the most sensitive designs.

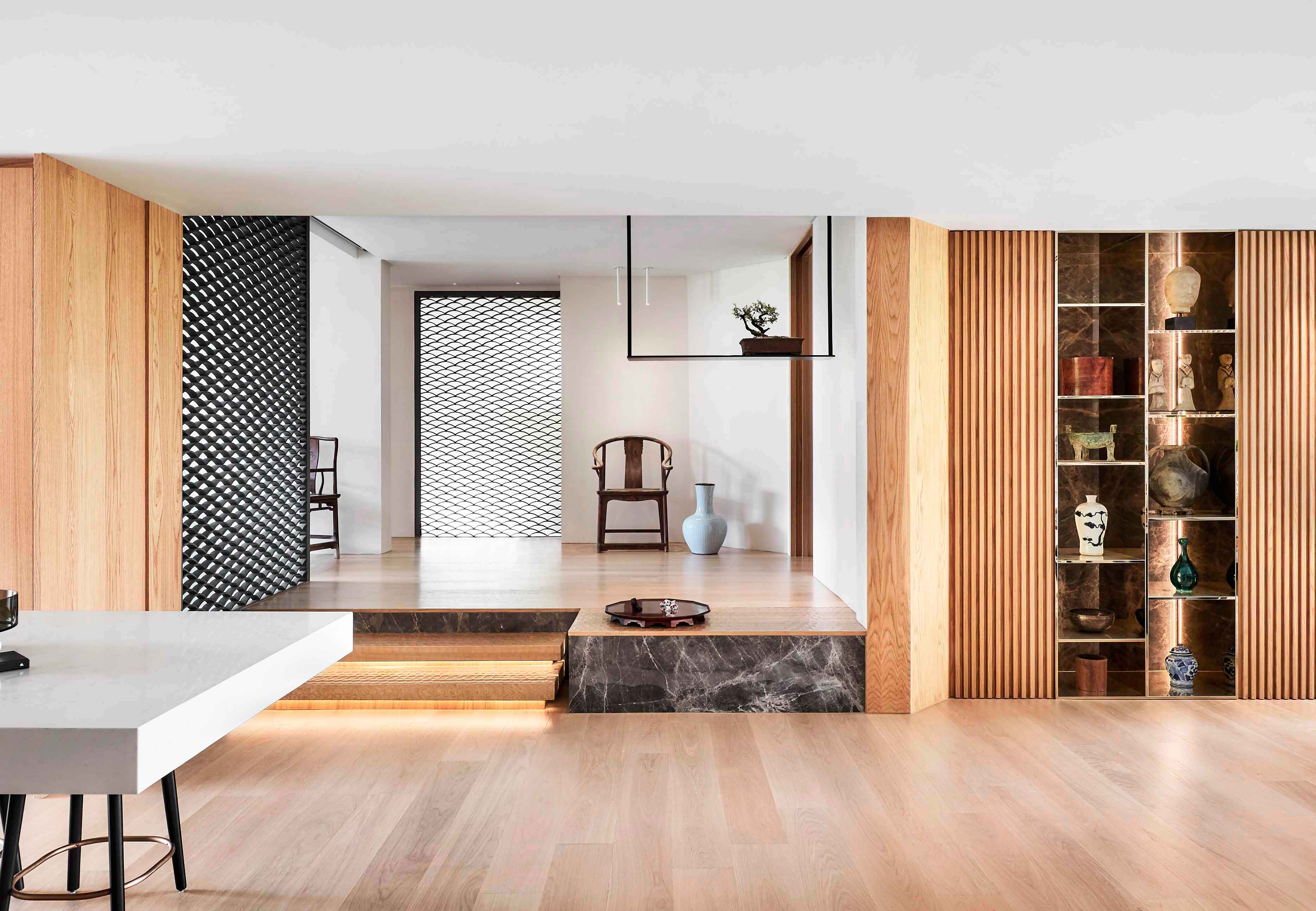

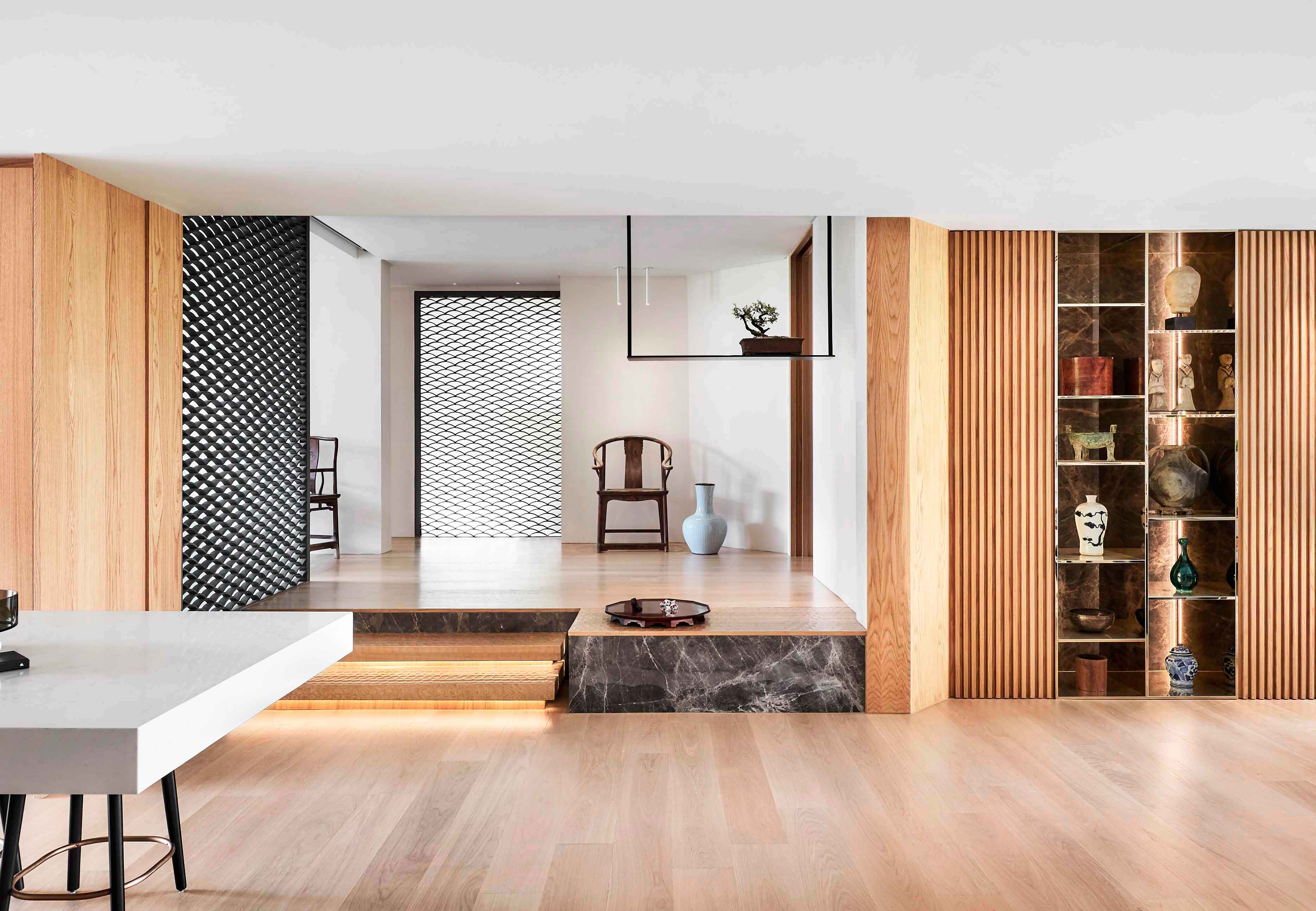

The foyer is enveloped in rhythmically detailed timber that neighbors with a traditional Japanese seigaiha-patterned wall made from Chinese roof tiles laid in waves, giving life to walls and beckoning touch. This vestibule opens up in several directions to carefully composed tableaux both immediate and far that sequence into layered vistas.

The apartment’s name gives clue about the aesthetic that inspired these touches. The homeowners are keen admirers of Japanese and Chinese cultures and wanted to evoke such sentiments in the renovation of the abode they had lived in for many years.

When not traveling, they work from home, so it was important that the environment was both restful and uplifting. It is housed in the red-bricked Nassim Mansion, built in 1977 and wrapped by matured heritage trees that form a lush curtain beyond the windows and balconies.

“Spatially, the 3,500-sqft apartment was sprawling yet underutilized, with isolated nooks and crannies. A tight kitchen space tucked away from the dining table and living room meant daily meals — an important time for the family — were oftentimes spent huddled in a tiny kitchen,” says Mr. Dennis Cheok, the principal designer of UPSTAIRS_ on the existing home’s faults.

Tiered levels between the living, dining and rooms — characteristic of condominiums built in the late 70s and early 80s — as well as diagonal columns in the plan’s center and rooms were isolating and awkward.

In the spirit of a ryokan, a traditional Japanese inn whose interior architecture is guided by fluidity, Mr. Cheok opens up the home physically through a series of spatial shuffles. An oversized powder room is reduced, and a new doorway cut into the kitchen wall to create two-way entry.

The latter now adjoins a dry kitchen across from the dining room, while a formerly shadowed, ambiguous area outside the bedrooms and study is now defined as a “courtyard.” Edged by a screen decorated with the seigaiha pattern — a unifying motif throughout the home — the courtyard formalizes the threshold between common and private activities.

“As a symbolic nod to the cloistered Japanese courtyards that interconnect the rooms and spaces of a ryokan, a Japanese bonsai suspended in miniature hovers upon a thin metal slat within this space, while a lacquered tray, evocative of a reflective pond, sits beneath it,” describes Mr. Cheok. This method of abstracting Japanese elements enables authenticity.

“The Japanese style is oftentimes reduced to stylistic kitsch: screens, washi, paper, tatami mats and the screens once again. To speak of style and stylistic tendencies as a design approach would already drive the end product within these limited devices.

“We had to dig deeper into the planning and experiential qualities instead and apply them to the contextual site. To conceive of each space this way would root us in the locale and the local, creating a distinctive response to a unique space,” Mr. Cheok expounds.

In another instance, a levitating naguri-textured plinth hand-carved from Japanese chestnut makes interesting footfall when transitioning from foyer to living room; this wonderful texture is again encountered as one steps up to the courtyard, and again in the master bedroom as the change in flooring subtly demarcates a seating area between the bed and balcony.

With such care taken in its selection and detail, the materiality of the interiors has an especially delicate personality. There is also wild-grained oak strip flooring, wire-brushed veneer paneling on walls.

An unsightly structural column at the foyer transforms into a sculptural object through oak veneer, curved edges and a slanted positioning. Spatially, it anchors the center of the main area, around which living, dining and kitchen navigate.

“We then built upon this blank canvas with lines, planes and sculptural volumes and objects, carving and inserting textures and colors at key moments of transition and pause,” explains Mr. Cheok.

The fluidity of the new plan enables these textures to be experienced as if one were walking through a gallery. They also give scale to the apartment’s expanse.

The layering motif works physically to connect zones, and thus chanced encounters among family members. Simultaneously, screens inject interest to this trajectory even as they filter light between zones.

The home is furnished in modern pieces, but Mr. Cheok also integrates the family’s beloved pieces harmoniously. For instance, a brassy niche backed by gray Athena marble in the dining room displays family heirlooms against a hefty, circular Molteni & C. Asterias dining table picked out by the clients, which Mr. Cheok combined with dark-toned Miss chairs from the same brand.

Throughout the home, Mr. Cheok orchestrates interplays of dark and light, modern and traditional. Across the dining room is a sleek, open-plan dry kitchen anchored by a 5-m-long island counter that now fosters unobstructed flow from food preparation to consumption.

Two light boxes — one as a platform underfoot and one on the table — further illuminate the area while concealing a horizontal plumbing pipe on the floor and a vertical riser pipe on the island’s center. Mr. Cheok envisions them as “lanterns” to brighten the kitchen at nightfall.

Such ingenious problem-solving is synonymous with Mr. Cheok’s meticulous attention to detail. For example, the naguri timber strips on walls, hand-carved by a sensei in Osaka, were particularly tedious to assemble, requiring a precise, numbered dry lay and custom connectors; the roof tiles forming the seigaiha patterns, being individually handmade, featured varying curvatures and the design team handpicked each to ensure they stacked up precisely.

Where the main areas have a lighter coloration, the bathrooms go the opposite direction, being wrapped in black marble and adorned with the charcoal-colored seigaiha roof tiles. “They are conceived as spatial counterfoils to the timber-clad main spaces, drawing upon the drama from shadows and reflections … they form the backdrop for the sculptural insertions of lines and planes: a plane-like, custom-built wash trough and the elongated lines of an IB Rubinetti gunmetal water sprout suspended from the ceiling in the powder room,” Mr. Cheok highlights.

He speaks of this project as one of his most challenging yet satisfying one to date. It’s no wonder why: The calming home now emanates beauty and practicality in equal measure.

Back

Back