On February 15, India’s space agency made history when it launched a flock of 104 satellites into space over the course of just 18 minutes -- that’s nearly triple the previous record for single-day launches. The sendoff was high-risk because the satellites were released in rapid-fire succession every few seconds from a single rocket as it traveled at over 27,000 km an hour.

But the feat was also significant for another reason: 88 of the satellites released were Doves, small five kilogram satellites manufactured by Planet Labs, a private company based in San Francisco.

Planet, which recently acquired Google’s satellite Earth imaging business, is a leader in the rapidly evolving field of space-based surveillance and communication. The company hopes that by launching large satellite constellations it can capture daily imaging of the earth’s entire landmass. And the India launch, which produced a 1,000-fold increase in data rates, has brought Planet closer to reaching its goal.

The implications are far-reaching. As the number of satellites orbiting earth increases (they have increased 40% in the past five years alone) and their imaging capabilities improve, commercial satellites are likely to influence everything from the stock market to how we respond to environmental disasters and run our farms.

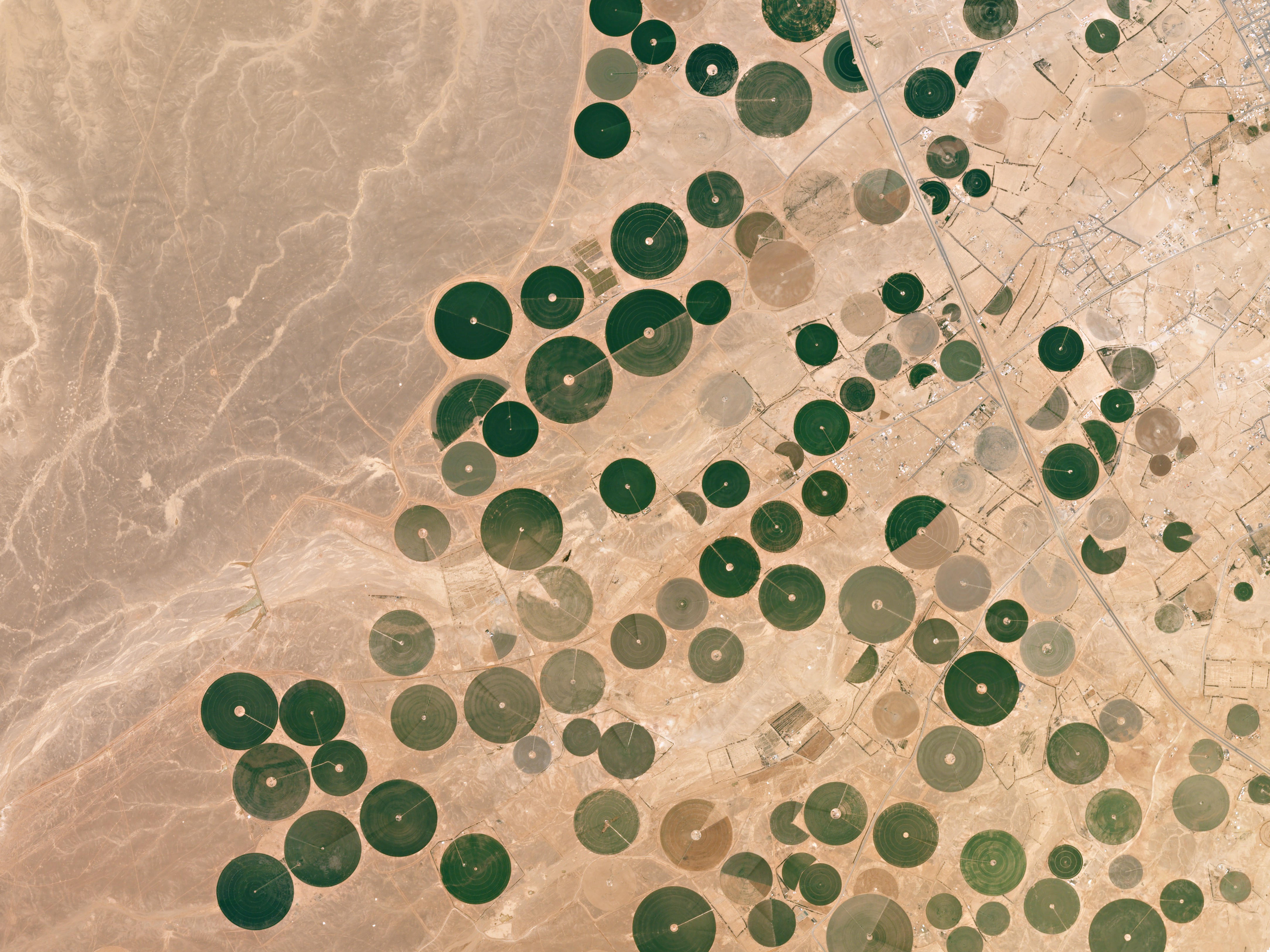

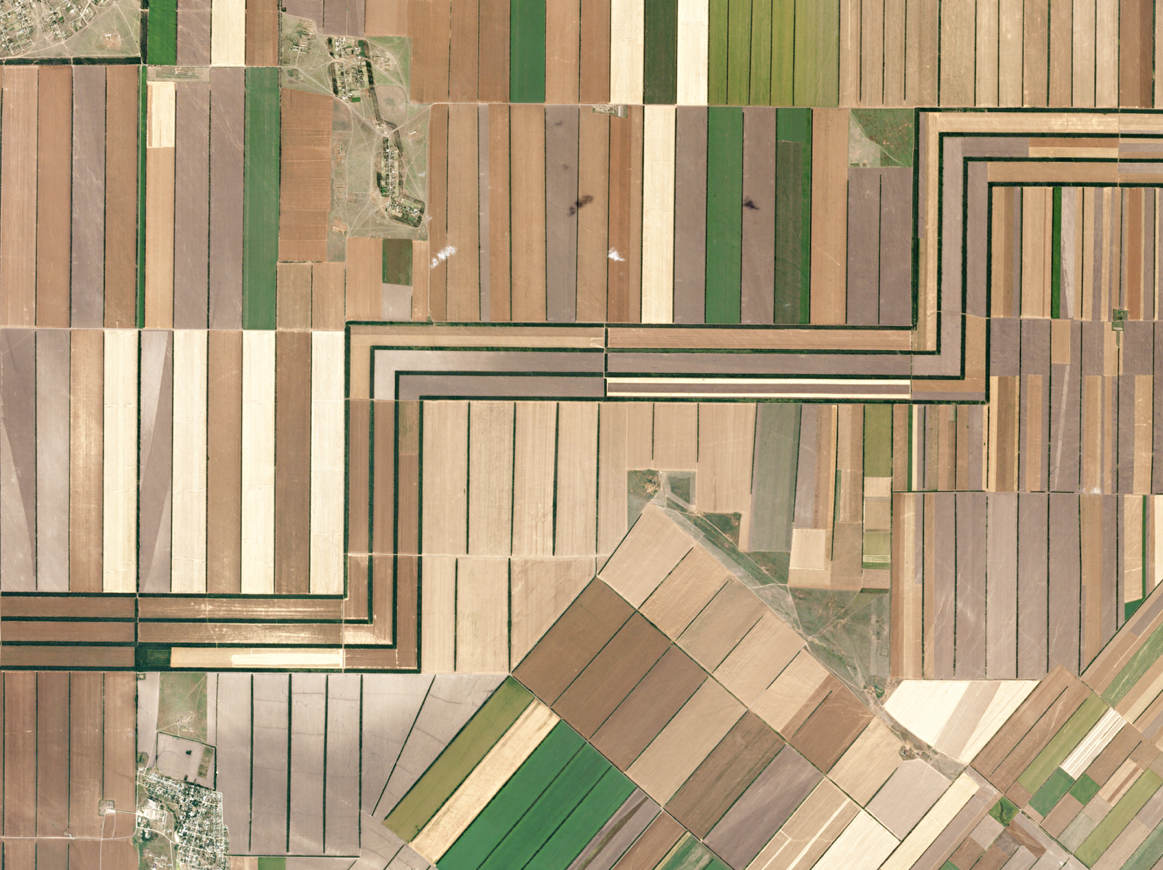

Planet Labs, which was founded in 2010 by three former NASA scientists, already has contracts with over 100 clients ranging from agriculture to government to Internet companies who want up-to-date pictures for consumer maps. “We can tell crop yield on a pixel-by-pixel basis for every farm around the world,” says Will Marshall, Co-Founder and CEO of Planet Labs. And the data is being used to precisely manage where and what to grow and when to plant, water, fertilize and harvest crops.

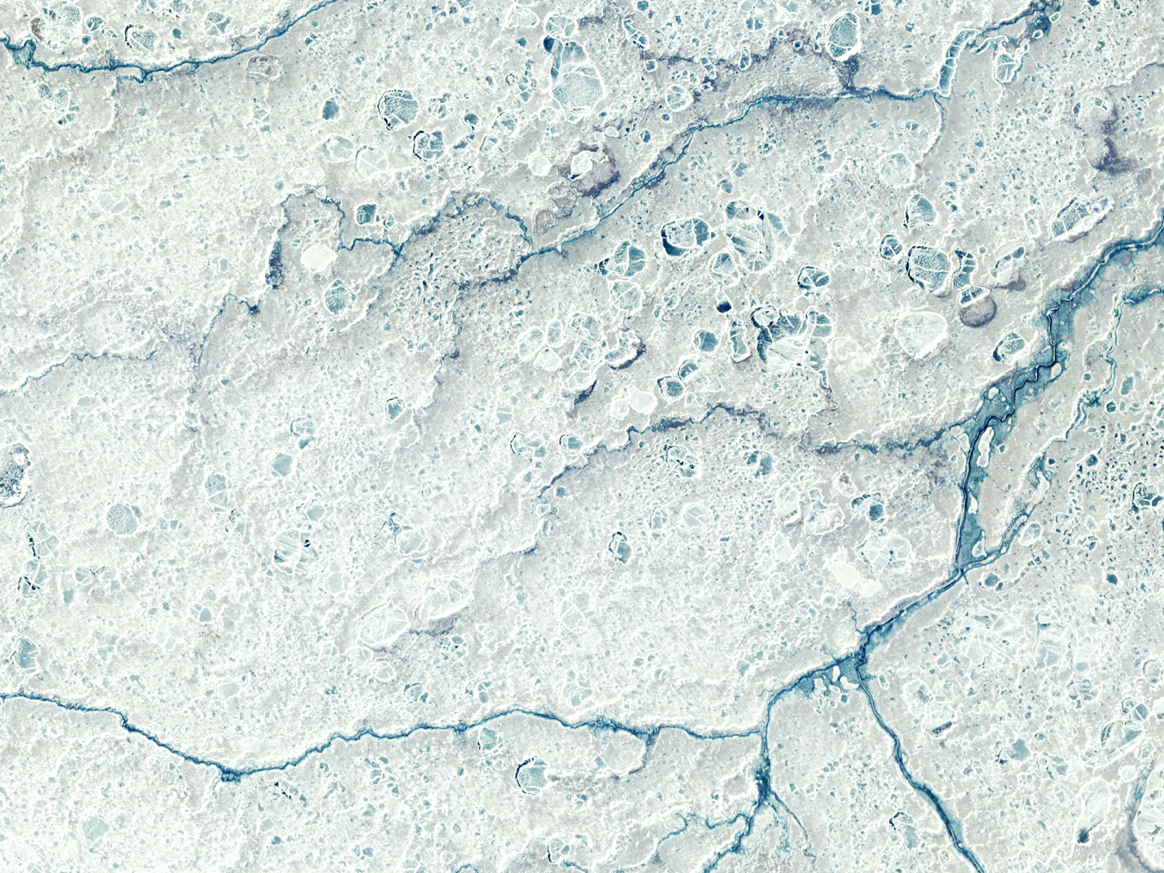

Indeed Planet’s satellites capture images with remarkably high resolution. From white snowdrifts in the Canadian interior to Florence’s densely packed terracotta roofs to the aquamarine patterns of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, the world’s beauty appears in full saturation. So too does its devastation. Gold mines, seaside industrial centers, deforestation and desertification are equally visible. And all of the data is readily available for download.

“We've built a data pipeline and software product that gets imagery data from space and onto a customers laptop in less than 24 hours,” explains Rachel Holm, director of communication at Planet. She says several companies in the Computer Vision and Machine Learning space now use Planet data to develop algorithms that can do everything from counting crops and commodities, to measuring the world's oil supply.

But while satellite imaging is often used for less charitable industries like defense and energy, the technology can also help with humanitarian causes. In addition to selling its data, Planet also provides imagery to NGOs and disaster relief agencies, as well as researchers who monitor everything from forest biodiversity to glacier dynamics to dolphin populations in the Amazon.

The data can also help to mitigate food shortages. According to the World Bank, the world may lose up 25% of its crop yields to climate change. But when geospatial information systems and remote sensing technologies are used in sync with satellite imaging, they are capable of precise food production forecasts and could provide enough lead-time to manage life-saving response.

By 2020 the global market for commercial satellite imaging is poised to surge to USD 5.3 Billion, according to the market intelligence firm Market Research Store. As the bearers of birds-eye views of world wield increasing power over the world they watch, let us hope the data also remains available to the causes that need it the most.

For more articles under The Future is Tech Special Report series, click here

Back

Back