“Given that, the adoption of biophilic design has to take into account the ‘un-adapted humans’ and make the transition gradual and incremental. It is not about forcing nature onto the residents, but avoiding designs that would paint ourselves to a corner and never allow nature into our living environment.”

Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson coined the term ‘biophilia’ in 1984 to describe humans’ natural attraction to nature and its elements, such as vegetation, flowing water, and sunlight, and denoting that environments with biophilic environments have psychosomatic benefits for their inhabitants.

“Biophilic design expresses and encourages the love for living things and living ecosystems,” elaborates Kuan Chee Yung, senior vice-president at CPG. “Most designs set in natural environments are already surrounded by natural living systems, and are often biophilic by immersion, but the challenge is to create biophilic designs in dense and predominantly mechanised and engineered urban settings.”

CPG’s history is intertwined with that of Singapore’s, given that the business was originally the Public Works Department of Singapore, corporatized in 1999. As such, CPG was involved in the design and construction of many iconic features of the Singapore landscape. Its pioneering work in the area of biophilic design is articulated in several notable projects across Singapore.

- GREEN VS. BIOPHIOLIC

- PUSH FACTORS

- SOME CHALLENGES

- READINESS AND ACCEPTANCE

Green vs. Biophiolic

Although they may have common charatceristics, ‘green’ or eco-conscious design is different from biopholic. “A building wrapped with solar panels can be green in terms of energy regeneration. A zero-energy closed-waste-system lifted on stilts above pristine wetlands can demonstrate eco-conscious design,” Chee Yung points out. “However, both buildings may not be biophilic in design if the occupants do not, by the quality and use of the spaces, or design patterns, feel a sense of affinity to the living things that surround them.”

This view of biophilic design might come across as purist, Chee Yung qualifies, but it is necessary to differentiate these seemingly similar design concepts. “For the laymen, a window to nature or a fish in an aquarium suffices to trigger the ‘parasympathetic system’ to enter a state of calm and balance. In other words, people automatically and subconsciously feel better when immersed in designs that remind them of nature.”

Various studies support the health benefits derived from biophilic design. For instance, patients living in hospital rooms with morning sun took 23 per cent less pain medication than those who were not, Chee Yung points out. “Biophilic design is also said to bring about positive effects on children’s health, specifically those suffering from ADHD, autism, and stress. It is also known to increase work productivity, elevate motivation, and lead to less absenteeism in office workers.”

Research has demonstrated that on one level, biophilic design brings a state of calm and balance when the body’s parasympathetic system is stimulated. On another level, the natural ecosystems integrated into the biophilic design can often improve the quality of air, allow natural light, filter and cleanse water, lower temperature, grow food, and so on, in built environments. “At its highest level, biophilic design brings together people who value and enjoy nature, and work together to protect and regenerate it,” says Chee Yung.

- GREEN VS. BIOPHIOLIC

- PUSH FACTORS

- SOME CHALLENGES

- READINESS AND ACCEPTANCE

Push Factors

Despite known benefits, transition from the overbuilt environment to one that is exposed to the elements may neither be simple nor easy. Chee Yung emphasizes that decades of migration from farmlands and fishing villages to living almost exclusively in man-made, highly serviced, urbanised settings has led us to forget what it is like to ‘give and take’ when living in natural environments or coexisting with other living things.

“Given that, the adoption of biophilic design has to take into account the ‘un-adapted humans’ and make the transition gradual and incremental. It is not about forcing nature onto the residents, but avoiding designs that would paint ourselves to a corner and never allow nature into our living environment.”

Natural systems, plants, and living creatures are not easy to maintain at stasis, as they are both aggressive in colonising and sensitive to change, Chee Yung explains. “Residents need to and want to understand and work with the ecology of plants and animals they are living with to fully develop mutual respect and enjoy each other’s company.”

But Chee Yung is optimistic that a massice change cannot be ruled out. Given Singapore's realities – population density, climatic condition, housing policy, future blueprint, sustainability – biophilic design may find ample use. “We have to understand that our ideal environment, food, and other resources cannot be generated by machines. These are done as a result of biological processes.

“We might not be able to generate authentic, howling, wild equatorial forests with the attendant large predators, but we can certainly regenerate parts of the riparian tree canopy and even scrubland zones in our network of green (trees) and blue (water) connectors, bioswales along roads and naturalised Active, Beautiful, and Clean (ABC) waterways. Our vertical green walls, green roofs, connected planters, artificial nests, interior terrariums, aquariums and paludariums do bring slices of nature deeper into our living spaces.”

- GREEN VS. BIOPHIOLIC

- PUSH FACTORS

- SOME CHALLENGES

- READINESS AND ACCEPTANCE

Some Challenges

What Chee Yung foresees as the limit is the people’s commitment and imagination, not the urban constraints. The use of biophilic features, he reasonsd, is ultimately akin to keeping a pet - plenty of commitment, understanding, and love for the living systems.

Biophilic design is practicable. Chee Yung explains that at its most basic – such as room with a view or community park – biophilic design is highly practical and acceptable, “to the point that I would insist it is a basic human right. However, delving into the intricacies would entail years of careful research and study to understand the ecosystem and how we are able to introduce life into it. Clearly defined goals and user commitment are also essential.”

Chee Yung proposes clear steps towards attaining biophilic design from where we are. “The first is to create access to users, enabling them to develop a visual connection with naturalistic features.

“Secondly, biophilic aesthetics like natural fractal patterns, ample daylight, and water features should be gradually added into the development.

“Finally, we should find opportunities to connect gardens internally and link them to a natural swale at the boundary - if one exists. This last step creates a floral bridge, which attracts fauna like butterflies, birds, and the occasional squirrel into the living spaces. One golden rule when we reach this final state is to not use pesticides and chemicals in the maintenance of the gardens and to keep artificial light, noise, and heat pollution to the minimum.

- GREEN VS. BIOPHIOLIC

- PUSH FACTORS

- SOME CHALLENGES

- READINESS AND ACCEPTANCE

Readiness and Acceptance

Planners, builders, contractors, designers, and other professionals ready to deliver biophilic design. “I’ve worked with many planners and industry professionals who are aware of the benefits of biophilic design and believe they are ready to deliver such architectural works. The driving factor that is not widely published is how biophilic design increases productivity and overall wellness to users of these development.

“As such, many parties in a development ‘value engineer’ inauthentic biophilic features without knowing the negative impact it can bring. One example is the often hidden and mechanically ventilated toilets within condominium units. These are a result of poor policy and perceived economic benefits of efficient floor plates.”

CPG, together with our enlightened clients and passionate statutory boards like NParks have pioneered and created many, if not most, of the instantly recognizable biophilic design buildings in Singapore, including the world’s first biophilic hospital, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital.

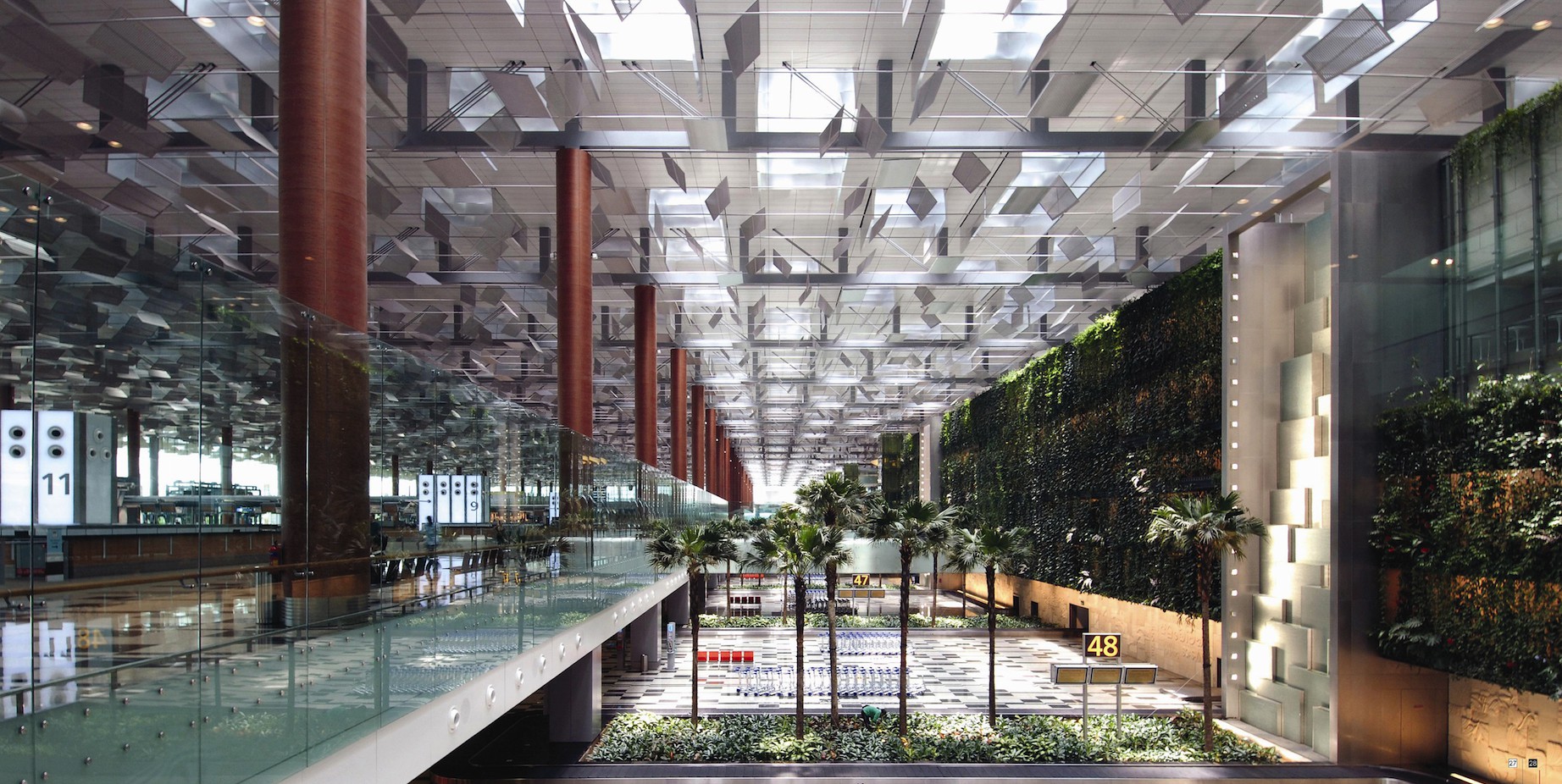

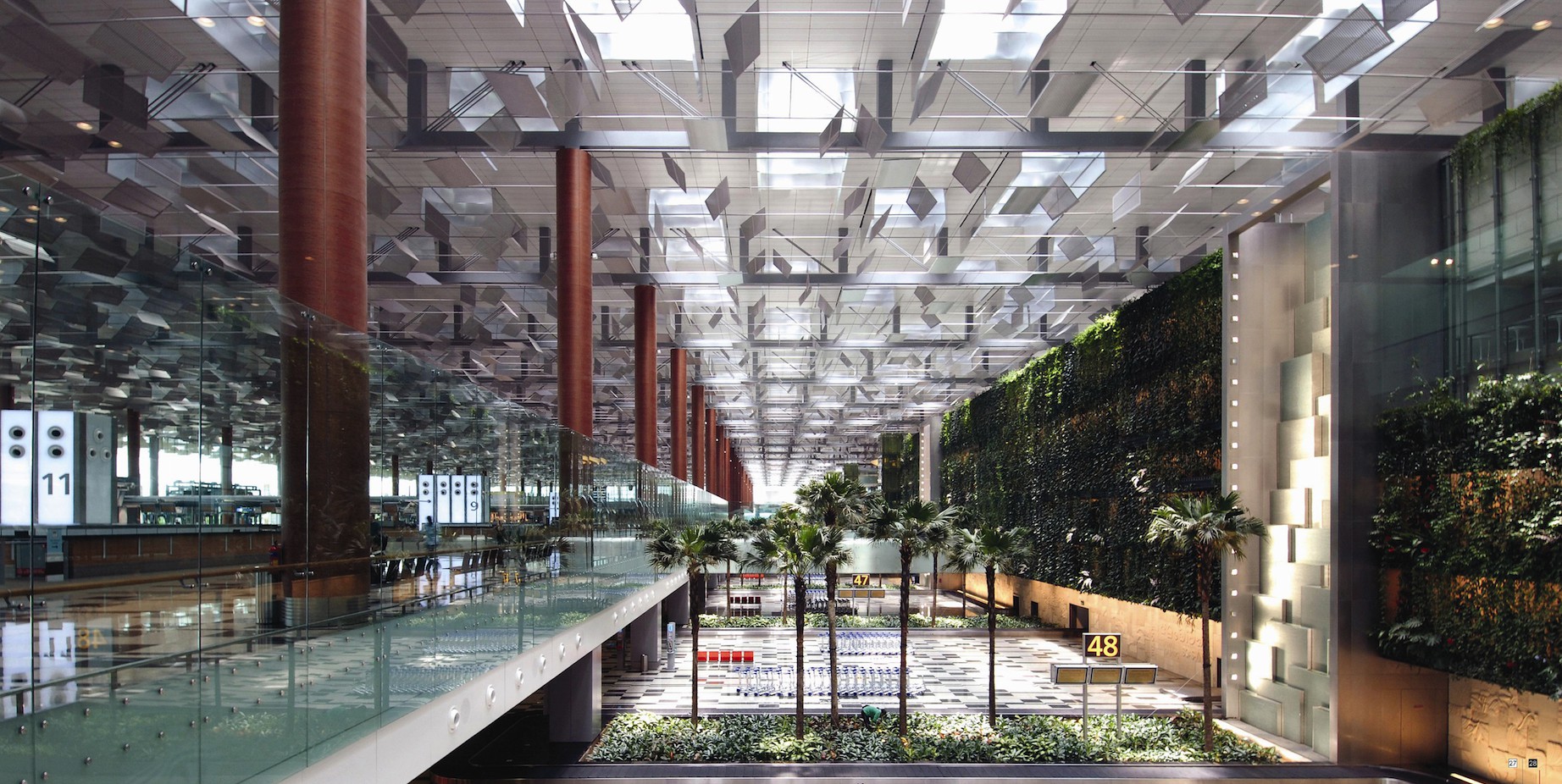

From creating the first touch point upon arrival at Changi Airport; visiting key attractions such as Gardens by the Bay; fostering conducive study environments in universities such as The Hive @ NTU; working in business parks and commercial facilities such as Solaris; exploring the nature reserves; and enjoying the ABC features of parks, CPG’s biophilic design hand constantly seeks to create these pockets of spaces that integrate nature with the man-made environment, unveiling another beautiful aspect of the tropical nature.

Back

Back